»Music for me at the moment is a heaven for non-believers.«

Abdullah Miniawy (born 1994) is an Egyptian expressionist, a writer, singer, composer, and actor. Over the years, he has shared the stage with acclaimed artists such as Erik Truffaz, Kamilya Jubran, Yom, Médéric Collignon, Aly Talibab, A Filetta, Hvad, Ziur, Simo Cell, and many others. Miniawy's performances have graced prestigious international stages and venues, including the Festival d’Avignon edition 72, French national theaters, Institute of Contemporary Arts London, Haus Der Kunst museum in Munich, Mao Asian Museum in Turin, even the Louvre in Paris.

In addition to his music career, Abdullah proved his natural acting talent in Alaadine Slim's Tlamess, a Tunisian feature film featured at the Directors' Fortnight at the Cannes Film Festival in 2019. Miniawy was also recognized with a nomination and shortlisting for the Best Actor Award from the Arab Cinema Center at Cannes.

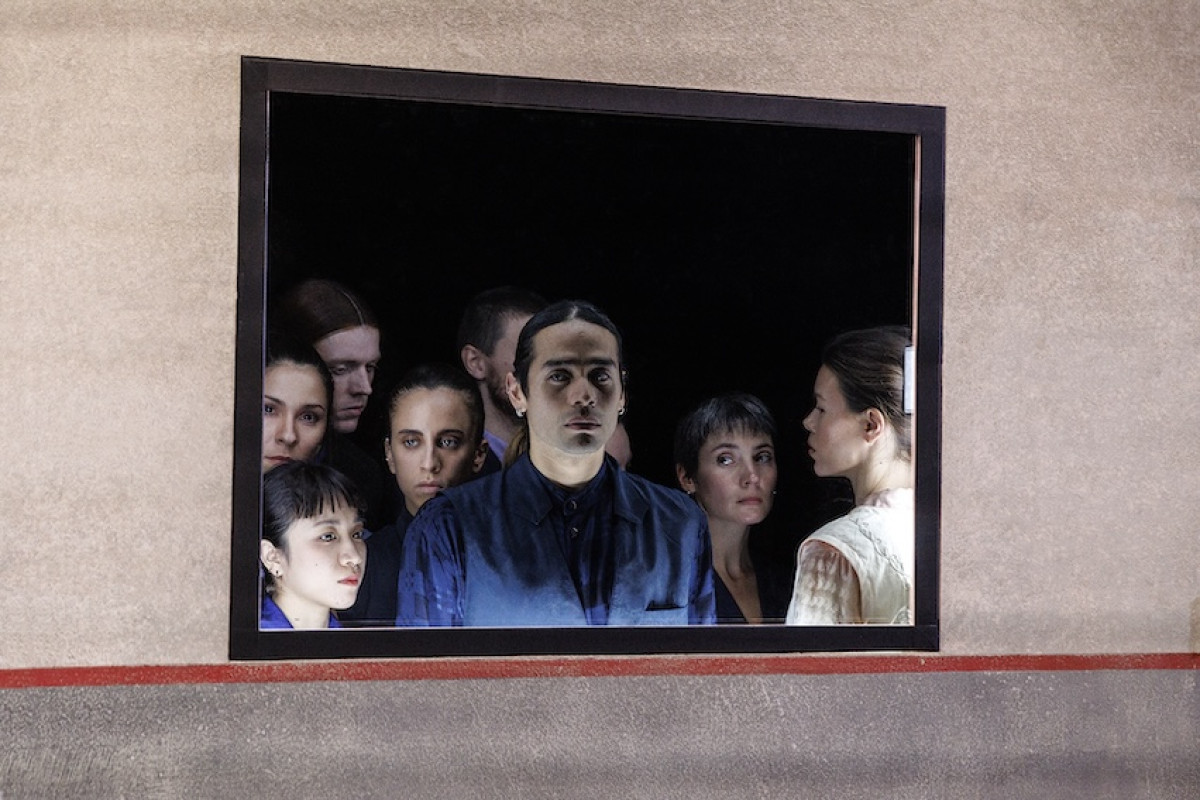

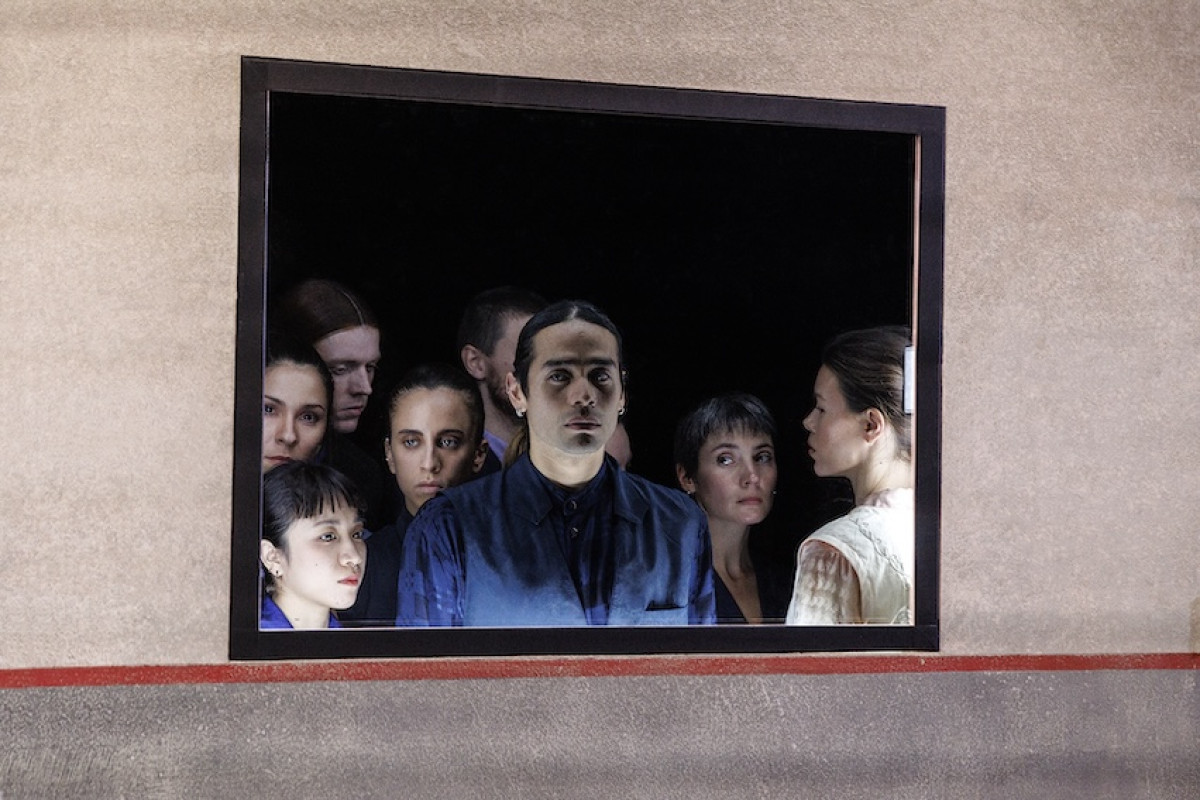

As a composer, Miniawy has created different soundtracks for dance shows, theater productions, and exhibitions, including notable works like Cabaret Crusade III by Wael Shawki premiered at Moma PS1, AMDUAT by Kirsten Dehlholm premiered at Hotel Pro Forma, and Insurrection by Jilani Saadi.

Abdullah Miniawy's influence extends beyond the arts; he was selected by the European Parliament in Strasbourg as one of three change makers from the Schengen area to offer a French-Egyptian artist's perspective on pressing contemporary challenges at the European Youth Event 2021 in the Live Fully section. He also participated in Europe Takes Part, a gathering of 30 diverse speakers discussing new economic models and digital solutions for artists in a post-pandemic world.

Since 2016, Miniawy has collaborated with the German trio Carl Gari, blending avant-garde electronic soundscapes with poetic lyrics. Their debut album, Darraje, was recognized as one of the top 50 albums of 2016 by the American NPR. Their recent release, The Act of Falling from the 8th Floor, garnered attention from Pitchfork, The Quietus, and Wire Magazine, with Zawaj ranking at the top of Resident Advisor's list of Deep Listening tracks in 2019.

Most recently, Abdullah's album Le Cri Du Caire, featuring Erik Truffaz, won Les Victoires du Jazz 2023 award – the French equivalent of the Grammy Awards.

As a writer, his lyrics have left a mark in the Middle East region, notably during the Arab Spring, where they were displayed in places like the Yarmouk camp in Syria.