»For me, music is all that vibrates.«

Bára Gísladóttir is an Icelandic composer and double bassist based in Copenhagen. Her work is generally based on thoughts regarding the approach and concept of sound as a living being.

Den danske Godfather af moderne elektronisk musik er ude med et formidabelt album – alt er skrevet og produceret af ham selv og partneren Lisbet Fritze, som optræder med sin angeliske og uimodståelige vokal. Ligesom Buster Oregon Mortensen (Busters Verden, red.) kan Trentemøller noget andre ikke kan, han har nemlig lært at trylle og med magiske formularer og tryllestøv har han skabt 14 skarptslebne skæringer.

Trentemøller mikser atter bastunge beats med svævende lethed og leger med grænserne for, hvordan han med uortodokse midler både kan skabe genklang hos et bredere publikum og samtidig dupere musiknørder verden over. Lytteren kommer med på indre rejser gennem alt fra »Glow«, der inviterer til clubbing med Autecre, »No More Kissing in the Rain«, som er en Trente-elektronisk fortolkning af indiepop a la Raveonettes samt en goth-industrial portal til den legendariske film Spawn: Nummeret »Dead or Alive«. Twin Peaks-mysticisme skinner igennem på »In the Gloaming«, imens man med »Drifting Star« drømmer sig væk i evige solnedgange.

Memoriams eklektiske tidløshed gør, at den på ingen måder er trendy men derimod langtidsholdbar og ville fungere forrygende som soundtrack til en film, TV-serie eller spil. Der er noget til Generation X, hipsterne, Jomfru Ane Gade og kosmopolernes natteravne. Uden tvivl en udgivelse, som vil vinde indpas i mangen en vinylsamling, være baggrundstæppe på tjekkede kaffebarer og gøre sit indtog på mixerpulte i underjordiske natklubber.

»For me, music is all that vibrates.«

Bára Gísladóttir is an Icelandic composer and double bassist based in Copenhagen. Her work is generally based on thoughts regarding the approach and concept of sound as a living being.

Allan Gravgaard Madsen’s and Morten Riis’s Away is a »mixed media« orchestral work. The physical orchestra is supplemented by sound and video recordings from the basement of Aarhus Theatre (woodwind quintet), Aarhus Cathedral (brass quintet), and Marselisborghallen (string orchestra). All of these locations have, at various points over the past 90 years, housed the Aarhus Symphony Orchestra.

Away opens with the final two chords of the overture to Rossini’s William Tell (1829), which are explored throughout the orchestra. Gradually, musicians leave the ensemble, only to reappear later in smaller constellations in recordings from the aforementioned locations. Through technology, the orchestra plays across time and space in a highly successful manner.

The work explores stasis and movement, with air as a central device: the wind players often blow into their instruments without producing tones, while the string players imitate the sound of wind using plastic bags. For me, Away has three highlights. Trumpets and percussion play phrases that turn out to anticipate a video of a flutist walking through the city. The trumpets mimic the sound of a truck – »beep-bop-beep-bop« – and the percussion becomes the flutist’s stilettos. Musique concrète turned on its head! At one point, half of the string players are seen sitting in a circle, playing intensely dissonant chords, only to kill them again – the physical shock activated my ears. The third highlight comes when the entire orchestra plays together again while all three projections are running simultaneously. Here, the work can truly begin, and one clearly senses the energy rising in the room. But – unfortunately – as soon as this climax is reached, the intensity drops again.

At just under 45 minutes, Away is, unfortunately, slightly too long and static for my taste. The effect of the aforementioned ruptures might not have been as strong in a shorter format, but I would have wished for just a bit more of the intensity the work so clearly was capable of delivering. I was left with a somewhat flat feeling. The piece also ended so quietly that several people were unsure whether it had actually finished and whether we could applaud.

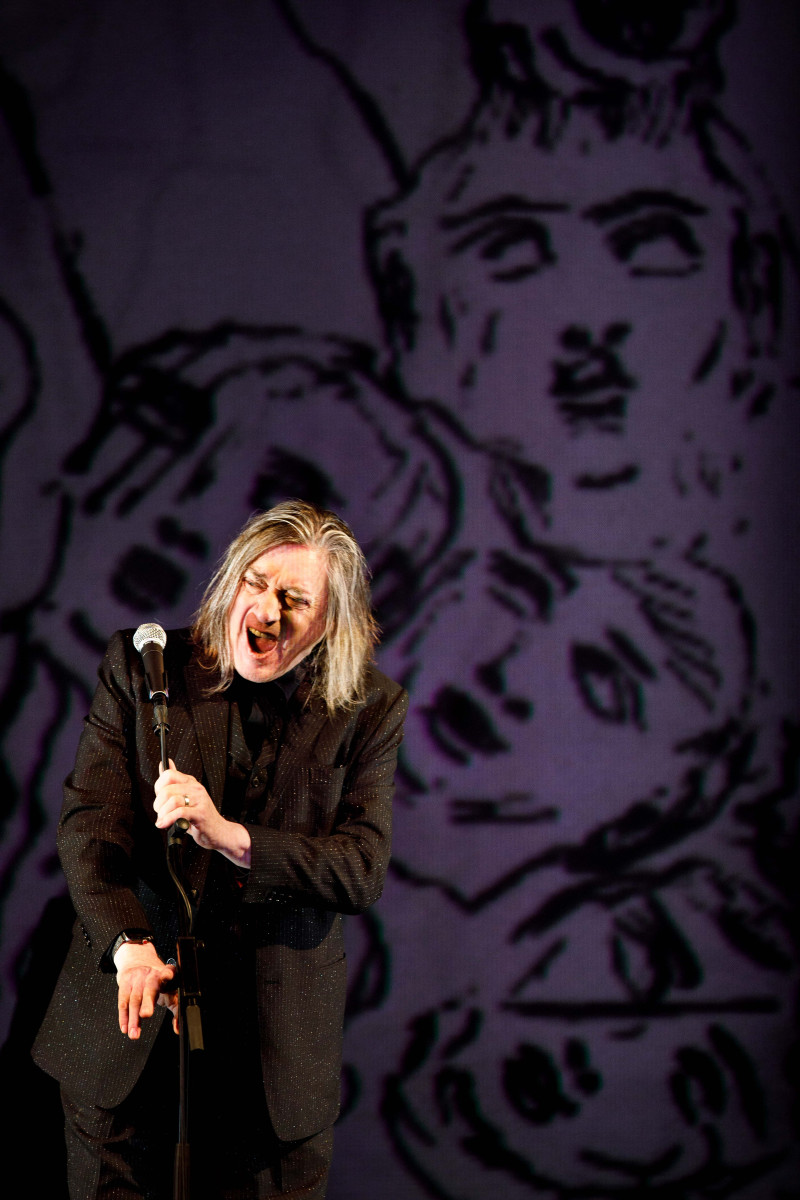

»All sounds are loud,« we hear in Flammenwerfer – Hotel Pro Forma’s account of the Swedish painter Carl Fredrik Hill (1849–1911). Everything in this universe is transparent and layered. The orange hue in Hill’s art, flickering across the stage, crackles with both a beautifully golden noise and a psychedelic quality reminiscent of 1970s ceramics. In a central scene, Blixa Bargeld half-screams into a microphone and receives looped screams hurled back into his head. The patchwork of sound also includes five vocalists from IKI and selected pieces – the only music here that comes close to pop – by Nils Frahm.

The dark circles under the eyes are constantly pronounced. As are the letters that signal a new chapter, the next dive into the mind – for instance the section titled »Paranoia«. Here, IKI expands Einstürzende Neubauten’s »Halber Mensch« into five voices, allowing the hallucinations and anxiety to grow to full human scale. Yes, the sound was loud and numbing in itself. But it is largely thanks to IKI that we feel the extremes, the brain disease, and Hill’s experience of a »misarranged world«. They sang: »Heavy curtains drawn over the mind. A thick deadening cloud that blocks the use of senses.« And that is how it sounded. Cold. Like the saddest Instagram filter imaginable – with sound.

Unfortunately, Blixa Bargeld is used too sparingly in Flammenwerfer, which is not exactly a masterpiece from Hotel Pro Forma. Still, the gala audience sat very still in very soft seats and saw both a giraffe and a former queen on the same evening. The rest of Aarhus Festuge can only be more cheerful.

»Music for me is bumping, rubbing, colliding, sliding and sculpting... in space-time. AKA the gift that keeps giving <3 .«

Greta Eacott is a critically acclaimed British/Swedish composer based in Copenhagen, Denmark. She is primarily known for her boundary pushing experimental percussion works and her »sans-disciplinary« approach to music composition; which incorporates spatial aesthetics, design theory and physical movements as integral elements in the musical compositions. This manifests in a unique and modern musical aesthetic which is both playful and refined, agitating and welcoming, sensual and synthetic. Since 2014 she has been running the DIY record label One Take Records.

If one had come to believe that new opera could only be starkly realistic portrayals of the world’s decay, Sky in a Small Cage at the Copenhagen Opera Festival would quickly prompt a rethink. The festival’s final work pointed in a completely different direction: mysticism, hope, love. All clichés, perhaps – but absolutely not in the hands of composer Rolf Hind and librettist Dante Micheaux. Together they have spun a truly astonishing opera about the Sufi poet Jalal al-Din Rumi.

It was as much the enchantment of Rumi’s poetry as the myth of the poet himself that drove the work. In fact, it was exhilaratingly difficult to distinguish between poetry and reality: the character Rumi became the object of his own grand poetic art. »It might as well be called a death: the gate you must go through to enter yourself or beloved,« sang a narrator-like figure at the outset. Love, one understood, is a self-annihilating transgression – a threshold phenomenon that at times demands its sacrifices.

This dreamlike doubleness served as a guiding principle throughout the performance. It was a pleasure to hear mysticism unfold in the music, which was phenomenally orchestrated with dripping gamelan bells and singing bowls, double harps, celebratory piano, and more pounding toms than Lars Ulrich would dare to dream of.

And what about the bird, the cage, and the idea of freedom? In Sky in a Small Cage, freedom was not a matter of opening the cage and setting the bird free. It was located in the very act of calling – in song, music, and poetry – as a reaching out toward the other in a kind of intoxication of love. Oh yes, the big questions are still alive in opera. Thank God.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek