Serious Creeps

Some dream of discovering life in distant solar systems. Others – like Knud Viktor, Jacob Kirkegaard and now also Simon Toldam – turn the telescope around and uncover unknown life in the immediate yet hidden nature surrounding us. So what did Toldam, the 46-year-old pianist from the experimental jazz milieu, find last night when he turned his gaze toward English photographer Levon Biss’s ultra-close images of beetles, flies and grasshoppers in the world premiere of the hour-long audiovisual trio work Insecta?

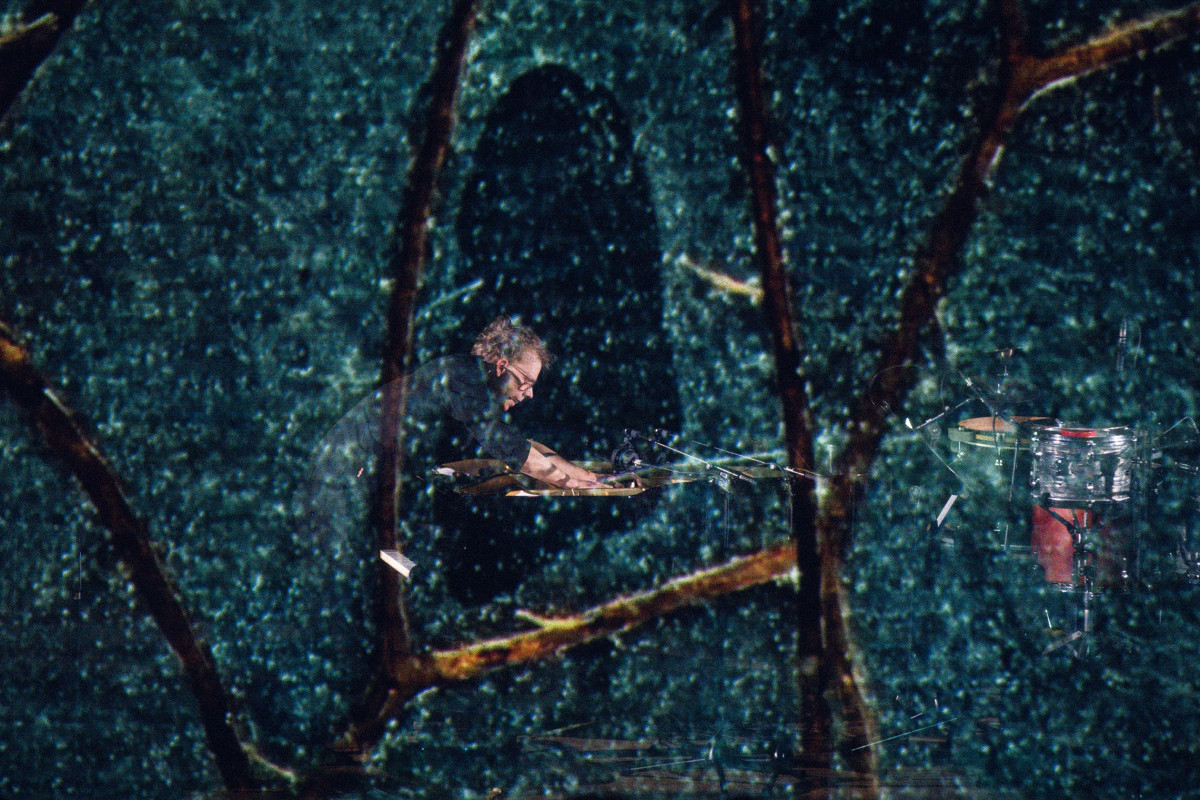

First and foremost, he found a varied and inquisitive interpretation of insect life. Behind a transparent screen, Toldam transformed his prepared grand piano into a kind of gamelan instrument, while on either side of him sounds crept and hissed from saxophonist Torben Snekkestad and percussionist Peter Bruun. The production values were high, and the trio – collectively known as Loupe – moved deftly between the concrete and the spherical.

At times, however, there was something old-fashioned about the expression. As a yellow-brown grasshopper gradually took shape on the screen, nanometre by nanometre, the piano’s metallic cymbal-sounds placed it within an Eastern sonic realm. It resonated with exoticism, with old electronic EMS recordings steeped in atonal serialism, and soon Snekkestad let a plaintive Miles Davis-like trumpet drift through the soundscape.

Yet when, with dramatic flair, he blew air through the same instrument or attached a rubber hose and transformed it into a frothing bass monster – while Bruun stroked metal surfaces or pounded the drums in ritualistic patterns – we were out of the past again. And when Insecta finally leaned into the ambient, and Toldam began bending the gamelan tones with his hands inside the open piano, it was as if not only time but also the distance between oneself and the insects dissolved into a trembling dream image. At that point, it suddenly no longer mattered whether there is life on Mars.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek

It is difficult to keep pace with Masami Akita. The 69-year-old Japanese noise artist, who since 1979 under the name Merzbow has helped shape the genre, released no fewer than a dozen albums in 2025 alone. On a rare mini-tour with stops in Helsinki, Stockholm and Aarhus, he showed that his energy remains intact. At Radar he gathered an audience that had travelled far to experience the godfather of noise – an artist who has consistently insisted on noise as a physical, almost tactile experience. Wearing a bucket hat, Akita constructed his trajectories with clear architectural precision. Layer upon layer of distortion and feedback took shape and struck like a brush of metal: hard, cutting, physical – uncompromising, yet at the same time remarkably nuanced.

Akita worked not only with electronics, but also with homemade metal instruments – first a banjo-shaped device, then a square musical saw – lending the sound a raw, tangible materiality. Everywhere, microscopic shifts in texture emerged, small fissures of tone within the massive pressure.

The opening set by frã (Francisco Moura) began the evening with a more fragile, yet persistent electronic texture, a precise counterpoint to Merzbow’s compact blocks of sound. Some might have wished for a gentler entry into the musical year 2026, but the concert underscored the ambitions Radar is currently pursuing.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek

The Excess of Attention

A steady stream of musicians enters the Xenon stage on Wednesday night at Vinterjazz. No fewer than 33 musicians take part in the mosaic of instruments assembled by the label Aar & Dag to celebrate the release of their cassette A MAJOR CELEBRATION. A release consisting of no less than three concerts, performed according to special composition cards, then mixed on top of one another and now issued on cassette. A major release calls for a major celebration, and rarely have I seen a more ambitious and idiosyncratic release concert.

The concert unfolded at a calm, unhurried pace – patient and attentive, the many musicians gave one another space to open up the broad soundscape. Double bass and electric bass, guitars, saxophones, synthesizers, percussion, cassette tapes, piano, and cello are just a selection of the orchestra’s many voices. Like a kaleidoscope, the ensemble shifted again and again, drifting between crooked, meandering passages and bubbling harmonies that only just brushed against a peculiar sense of tempo.

The word »soundscape« truly comes into its own in this context. For much like Hieronymus Bosch’s surreal monumental paintings or Sven Nordqvist’s Pettson and Findus illustrations, the concert – with its many people on stage – was filled with an impressive level of detail and a multitude of small scenes unfolding across one another. Each time my attention settled on a particular point in the music, I missed a new development elsewhere in the orchestra. An excess of attention, and a fine demonstration of a boundary-disrupting musical expression that one can only hope to encounter more of.

All Life Has the Right to Live

It is this violent and feral line of text that hangs like a monolith in the austere stage space at Sort/Hvid after 80 minutes of a furious, raging monologue in the performance Animal. Actress Signe Egholm Olsen is left standing like an animalistic goddess who has carried out her own ritual of purification. A ritual about motherhood and about morality for animals and humans alike – flanked by the three wordless classical singers Katinka Fogh Vindelev, Nina Smidth-Brewer, and Hávard Magnussen, who function as a chorus in a Greek tragedy. They illustrate and stage the text through precise sonorities.

Animal is based on Alexandra Moltke Johansen’s debut novel from 2022 of the same name and overflows with meaning, hurled into the audience’s face from beginning to end. Worries, anxiety, angry activism, grief, and doubt – tied to being pregnant and becoming a mother to a »useless« child with Down syndrome in a world marked by climate catastrophes, war, inhumane political cynicism, and greed. All of this flows from the mother’s inner dialogue as a long moral reckoning and outpouring, unfolding in a scenic tour de force – from the clinically clean and artificial atmosphere of a wellness spa to a material chaos of soil, branches, and sweat.

Kirstine Fogh Vindelev has composed a soundscape that makes it possible for us to breathe at all. Discreet choral tones, small electronic passages, a touch of barbershop, screams, and a pop song are wedged in between the words. It is simple and straightforward. The music is allowed to comment and converse like a shadow presence alongside the many words, but at no point is it allowed to become the protagonist or truly carve out its own space within the performance. One could easily wish for another form of sensory reflection than that which words and speech alone can provide.

14 Meters of Wave Swells from History’s Anonymous Depths

Sound artist Jacob Kirkegaard records sounds to connect with the world – to endure what is happening. This time, it's a commissioned work for the Museum of Copenhagen, created to accompany the exhibition of an excavated shipwreck from the harbor. The result is Naufragium (Latin for shipwreck) – gently lapping, quiveringly simple, and almost self-effacingly discreet. And in this way, everything aligns: the story of life in the harbor during the late Middle Ages is only known through rare, major events, while the bustling everyday life, connecting it to the larger world, has drowned in anonymous oblivion.

The shipwreck itself is barely recognizable. A series of ship planks – up to 14 meters in length – suspended on mirrors and supplemented by 11 crossbeams. That’s it. The light in the museum’s narrow room is dimmed, and the windows are covered with film. We are submerged into the depths of the water.

The sound loop lasts 39 minutes if one wishes to listen to it in full. Small sounds are distributed across seven speakers – four in the ceiling, three beneath the wreck. Carefully placed, the gentle lapping, dripping inserts, a trembling rustling like a nerve pathway above, and muffled sounds of wood shifting in water are heard. A kind of foghorn also makes an appearance. All of it is subtly arranged as a soundscape for a silent protagonist, staged through sound. There were likely very few storms, cannons, or other forms of grand drama in the ship’s perhaps 300 years as a cargo vessel in the Copenhagen Harbor before it sank in the 18th century. But if one looks closely – and opens their ears – it bears tangible and truthful witness to the kind of history most of us inherit: the ordinary one.

Echoes from a Forgotten Time

The abstract, collage-like »Movements« on Lebanese artist Raed Yassin's Phantom Orchestra are yet another piece of contemporary art born out of the COVID-19 crisis. Like a distant echo from a time most have already repressed, the experimental artist has assembled a series of recordings performed by a motley group of Berlin musicians – all united by a single premise: improvisation.

Over nearly an hour, Yassin weaves these recordings into seven progressive suites, ranging from approximately nine to twenty minutes. And while the sonic chaos at times reaches such heights that one struggles to find a common auditory anchor, the result is a creatively stimulating listening experience, as hand-played percussion, Baltic folk singing, and the Japanese koto (harp) seamlessly merge – despite the musicians never having been in the same room together.

At its core lies an immensely inspiring concept, one that draws equally from sampling aesthetics and contemporary art. This is particularly evident considering that the pieces were reportedly created using no fewer than twelve turntables, introducing an element of chance. One can only assume that this required a remarkable degree of planning – which makes it all the more astonishing when, for instance, the interplay between modular synths and drums on »Movement III« unfolds, or when the almost horror-like contrast between happy jazz trumpet, frantic vocals, and demonically prepared piano emerges on »Movement IV«.

At times, the idea behind the work is more fascinating than the sound itself, but all in all, Phantom Orchestra is a dazzling, slightly mad experiment, driven by a will to create harmony in chaos. A final echo of the pandemic – of standing together while apart.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek